The Dangers of Long-Term Poor Sleep

Chronic insufficient or poor‑quality sleep disrupts multiple interconnected physiological systems. During consolidated nighttime sleep, the brain and body orchestrate circadian and homeostatic processes that regulate endocrine secretion, neuronal restoration, immune surveillance, cardiometabolic balance, tissue repair, and cognitive integration. Persistently short sleep duration, irregular timing, fragmented architecture (frequent awakenings, reduced slow‑wave and REM sleep), or excessive long sleep associated with underlying illness can each signal or precipitate pathology.

Endocrine regulation becomes dys-synchronized when sleep is curtailed. Growth hormone pulses, gonadal hormone modulation, thyroid axis fine‑tuning, and melatonin secretion depend on intact sleep timing and light–dark cues. Sleep restriction heightens sympathetic nervous system activity and elevates evening cortisol, contributing to impaired glucose tolerance, increased hepatic glucose output, reduced insulin sensitivity, and higher risk trajectories for type 2 diabetes. Leptin concentrations may fall while ghrelin rises, amplifying appetite and preference for energy‑dense foods, further compounding metabolic strain.

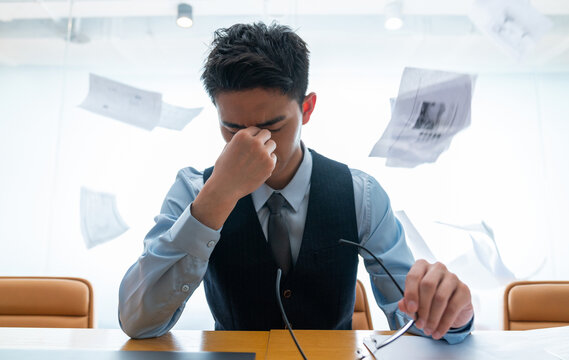

Neurocognitive consequences emerge through impaired synaptic down‑selection, diminished glymphatic clearance of metabolic by‑products, and stress‑mediated neurochemical shifts. Functional deficits manifest as slowed processing speed, reduced working memory capacity, attentional lapses (microsleeps), executive dysfunction, and mood lability. Prolonged elevation of stress hormones has been associated with structural and functional alterations in hippocampal circuitry, potentially influencing memory consolidation and emotional regulation.

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems rely on nocturnal declines in blood pressure (the “dipping” pattern), heart rate, and sympathetic tone to maintain endothelial health. Habitual sleep <6 hours or, in some cohorts, >9 hours, correlates with increased incidence of hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, arrhythmias, and atherosclerotic progression, independent of traditional risk factors. Mechanisms include heightened inflammatory signaling (C‑reactive protein, interleukin‑6), oxidative stress, autonomic imbalance, and metabolic dysregulation.

Immune competence deteriorates with chronic sleep deficiency. Natural killer cell activity can decrease, vaccine antibody responses attenuate, and pro‑inflammatory cytokine profiles shift, creating a paradox of baseline low‑grade inflammation with reduced targeted pathogen defense. Tissue repair and barrier function may be delayed, and susceptibility to viral infections rises during periods of sleep curtailment. Adequate slow‑wave sleep supports anabolic processes that facilitate musculoskeletal recovery.

Dermatologic and connective tissue manifestations reflect impaired microvascular perfusion and altered collagen turnover. Poor or irregular sleep is associated with increased transepidermal water loss, reduced skin elasticity, accentuation of fine lines, periorbital darkening, and delayed wound healing. These changes may be compounded by systemic inflammatory mediators and circadian disruption of fibroblast activity.

Mental health vulnerabilities are both a cause and consequence of disordered sleep. Insomnia and circadian rhythm disturbances elevate risk for anxiety and depressive disorders; conversely, mood and anxiety conditions often fragment sleep, creating bidirectional reinforcement. Altered reward processing and stress reactivity can precipitate maladaptive coping behaviors (emotional eating, substance use), while chronic sleep debt may contribute to dysregulated hair follicle cycling in susceptible individuals, modestly increasing hair shedding complaints.

Metabolic housekeeping processes—including autophagic turnover, clearance of cellular debris, and modulation of inflammatory signaling—are modulated during sleep, and persistent disruption can impair joint and muscle recovery, sustaining daytime pain or stiffness. Over time, cumulative multi‑system effects of poor sleep increase all‑cause morbidity risk and degrade quality of life.

Addressing chronic sleep problems involves optimizing sleep hygiene (consistent schedule, light management, environment control), screening for primary sleep disorders (obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, circadian rhythm disorders), managing comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions, and employing evidence‑based behavioral interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT‑I). Prioritizing restorative sleep is a foundational preventive health strategy with wide‑ranging systemic benefits.