Normal CT Anatomy of the Spinal Canal, Intervertebral Discs, and Spinal Cord

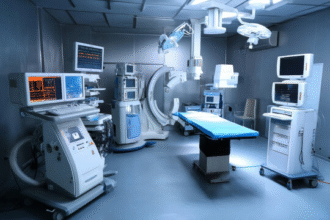

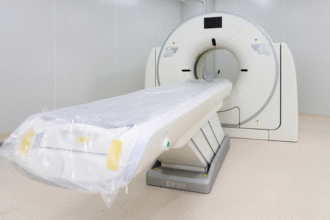

Understanding the normal cross‑sectional anatomy of the spine on computed tomography (CT) is essential for distinguishing physiological variants from pathology and for accurately localizing degenerative, traumatic, infectious, neoplastic, or congenital abnormalities. CT provides exquisite depiction of cortical and trabecular bone, reliable delineation of intervertebral disc margins, and indirect evaluation of the spinal cord and nerve root compartments when combined with appropriate window settings or intrathecal contrast (in CT myelography). Although MRI excels in soft tissue characterization, CT remains indispensable for osseous detail, acute fracture assessment, and preoperative planning.

Vertebral body morphology changes progressively from the cervical through thoracic to lumbar regions. In axial sections the vertebral body typically appears oval or kidney-shaped with a slightly flattened or concave posterior margin; in sagittal and coronal reformations it is rectangular. The vertebral body size increases caudally, reflecting load-bearing demands. Normal trabecular architecture presents as a finely textured cancellous matrix bounded by a dense cortical shell. Posterior elements (pedicles, laminae, transverse processes, articular facets, spinous process) form the vertebral arch, completing a ring that encloses the spinal canal. Subtle cortical interruptions, irregular endplate concavity, or asymmetry of pedicle dimensions should prompt correlation for fracture, lytic lesion, or developmental anomaly.

The spinal canal on CT is evaluated by its sagittal anteroposterior (AP) diameter, transverse diameter, and cross‑sectional area. The cervical canal is widest at C1 and gradually narrows toward the mid-lower cervical levels, with clinically useful lower AP thresholds approximating the mid-teens in millimeters; marked narrowing raises concern for congenital or acquired stenosis. Thoracic canal dimensions are relatively uniform and mildly rounded; the average AP diameter resides in the mid‑teen range. Lumbar canal size typically ranges broadly within the mid‑teens to mid‑twenties millimeters AP, with subtle tapering or widening influenced by pedicle morphology and ligamentous structures. Recognizing proportional regional differences is more important than memorizing absolute numeric cutoffs, which vary with patient habitus and measurement technique. Focal encroachment by facet hypertrophy, ligamentum flavum thickening, epidural fat proliferation, or disc material should be interpreted against this baseline.

The sacrum, formed by fused sacral vertebrae, appears on axial CT as a broad upper segment narrowing inferiorly into a ventrally concave triangular bone. Its transverse dimension is typically greater in females, relevant to pelvic biomechanics. Transitional lumbosacral anatomy—partial sacralization of L5 or lumbarization of S1—may be encountered and must be numbered carefully (often using the last rib-bearing vertebra or whole-spine scout) to avoid wrong-level intervention.

Ligamentous structures are variably appreciable on standard non-contrast CT. The ligamentum flavum, positioned symmetrically along the posterolateral spinal canal between laminae and facet joints, may appear as a thin soft tissue density band. It is relatively thin in the cervical region and thickest in the lumbar spine; focal or diffuse thickening beyond typical margins can contribute to central or lateral recess stenosis. The posterior longitudinal ligament is usually indistinct unless calcified. Awareness of expected ligament contours prevents mislabeling mild prominence as pathologic.

The lateral recess—an anatomic corridor within the epidural space—extends from the lateral dural sac margin toward the entrance of the intervertebral foramen. It is bounded anteriorly by the posterior vertebral body and disc, laterally by the pedicle, and posteriorly by the superior articular process and ligamentum flavum. Symmetry is expected. Diminished anteroposterior depth relative to the contralateral side or absolute effacement by facet osteophytes, disc protrusion, or soft tissue mass may herald nerve root compression. Measurements are technique-dependent; interpretation should emphasize comparative morphology and the presence of superimposed degenerative changes.

Epidural fat provides natural negative contrast outlining the thecal sac and nerve root sleeves. On axial CT, fat planes are typically seen anterior to the dural sac (between disc and thecal margin) and bilaterally within lateral recesses and foraminal extensions. Loss of normally lucent epidural fat can suggest space-occupying processes such as disc extrusion, epidural hemorrhage, phlegmon, or neoplasm; conversely, exuberant epidural lipomatosis appears as concentric low-density expansion compressing the thecal sac.

Intervertebral discs display attenuation greater than cerebrospinal fluid yet lower than adjacent bone. Their axial contour is generally ovoid or kidney-shaped with a gently concave or straight posterior margin that should remain flush with or minimally beyond the posterior vertebral body line. Cervical discs are thinner than lumbar discs and may exhibit physiologic anterior greater than posterior height. Thoracic discs are the thinnest, corresponding to reduced mobility. Subtle focal posterior contour extension, focal density heterogeneity, or vacuum phenomenon (intragas accumulation) requires correlation for degenerative changes, herniation subtype, or instability. Thin-section acquisition (≤1–1.25 mm) enhances detection of annular fissures, calcifications, and small extrusions.

The spinal cord is centrally situated within the dural sac from the foramen magnum to the conus medullaris, which typically tapers around the L1 vertebral level (with normal variation). Standard non-contrast CT depicts the cord indirectly via surrounding cerebrospinal fluid attenuation difference; intrathecal contrast in CT myelography accentuates cord and root sleeve margins. High-resolution techniques or favorable patient habitus may allow recognition of slightly lower attenuation gray matter centrally compared to peripheral white matter, although MRI remains superior for intramedullary detail. The cervical cord on axial images is elliptical with a subtly flattened anterior surface (anterior median fissure) and a faint posterior midline dimple (posterior median sulcus). Thoracic cord sections appear more circular, with less conspicuous surface landmarks. Caudal to the conus, the cauda equina nerve roots descend in parallel strands within cerebrospinal fluid, sometimes coalescing into punctate or linear soft tissue densities on thin-section images.

Recognition of normal caliber transitions—cervical and lumbar enlargements reflecting neuronal plexus aggregation—is critical to avoid misinterpretation as swelling. Uniform attenuation, preserved surrounding cerebrospinal fluid margin, and absence of extrinsic mass effect support normalcy. Apparent cord or cauda equina distortion should prompt evaluation for extrinsic compression (disc herniation, ossified posterior longitudinal ligament, epidural collection) or intrinsic pathology (tumor, demyelination) on correlation imaging.

A systematic interpretive approach on CT begins with vertebral alignment and body integrity, proceeds to posterior elements and facet congruity, evaluates canal and foraminal patency, inspects disc contours and density, assesses ligamentous and epidural fat planes, and finally verifies cord position and contour. Familiarity with normal numeric ranges is helpful, yet pattern recognition of proportion, symmetry, and preserved fat interfaces is often more reliable in early or subtle disease detection. Employing appropriate bone and soft tissue window settings and using multiplanar reconstructions (sagittal, coronal, oblique) significantly increases diagnostic confidence.

In summary, normal CT anatomy of the spinal canal, discs, and spinal cord reflects harmonious relationships among osseous, ligamentous, neural, and adipose structures. Mastery of these baseline appearances underpins accurate identification of pathologic deviation, optimizes intervention planning, and enhances multidisciplinary communication.

Disclaimer: Educational reference; correlate with MRI or CT myelography when detailed neural element evaluation is clinically required.